The Real Thing?

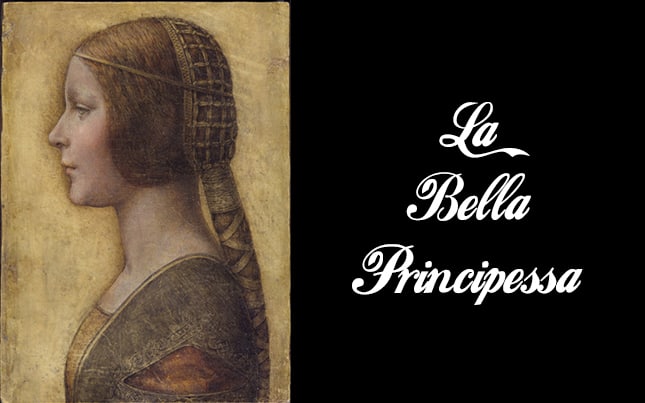

A fingerprint has intensified the debate about the origin of a mysterious drawing sold at auction for $21,850. Experts don’t agree whether it’s a 19th–century German work or a genuine Leonardo worth $150 million.

Is it a bargain Leonardo da Vinci picked up under the noses of connoisseurs or is it just an old German drawing?

That’s the $150 million question that art scholars in Europe and the United States are asking about La Bella Principessa.

The drawing, depicting a young woman in profile, was bought by a dealer as “German School, early 19th century” at a Christie’s auction in New York for $21,850 in 1998 and resold for $19,000 in 2007 to a Canadian collector who says he bought it on behalf of a Swiss collector.

The debate has intensified in recent months with the disclosure of what has been described as Leonardo’s fingerprint near the top of the drawing, revealed in new photographs taken by a high–resolution multispectral camera.

The dispute over La Bella Principessa is the latest of the attribution battles that have been unfolding in the art world for more than 100 years. Some of the disputes have been conducted in what one writer said was “gentlemanly but deadly earnest fashion.” The antagonists in the Leonardo brouhaha have behaved in a similar fashion thus far, although other attribution controversies have not been so gentlemanly.

So is the drawing really a Leonardo?

“I have no doubts at all,” Martin Kemp, who is considered one of the world’s most brilliant Leonardo specialists, told me recently in a telephone interview from his home in Woodstock, England. He is professor emeritus of art history at Oxford University and has spent more than 40 years studying Leonardo. Kemp, who gave the drawing its name, believes that the subject is probably Bianca Sforza—the illegitimate daughter of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan—who was born in 1483.

I asked Klaus Albrecht Schröder, director of the Albertina in Vienna, about the rumors that he had been asked to exhibit the drawing. “We decided we would not show it because we are not convinced that it is an authentic drawing by Leonardo,” he told me in a telephone interview. “It was examined by our own research center, our curators, our restoration department, and the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. No one is convinced that it is a Leonardo.”

Otto Naumann, a prominent New York dealer in Old Masters, valued the drawing at $150 million, “contingent upon uncontested attribution.”

Among the scholars who agree with Kemp is Alessandro Vezzosi, director of the Museo Ideale Leonardo Da Vinci in Vinci, Italy, Leonardo’s birthplace. Vezzosi included the drawing as a Leonardo in a monograph he published in 2008. “Of course there can be surprises,” Vezzosi told Judith Harris, who writes for ARTnews in Italy. He said he is “convinced it can only be by Leonardo, on the basis of its quality, style, iconography, and its being the work of a person who is left–handed,” as was Leonardo.

Mina Gregori, professor emerita at the University of Florence and doyenne of Italian art historians, told Harris that “the purity of the profile and the Florentine topology of the face” had convinced her that the drawing was by Leonardo.

Carlo Pedretti, Armand Hammer Professor Emeritus of Leonardo Studies at UCLA, wrote in an introduction to Vezzosi’s book that the work constitutes “the most important discovery since the early nineteenth–century re–establishment of the Lady with the Ermine in Krakow as a genuine work by Leonardo.” But he cautioned that “the insidious possibility of a fake must always be considered, bearing in mind the ability of an artist like Giuseppe Bossi (1777–1815), a noteworthy Leonardo scholar, who assembled a distinguished collection of drawings by the artist, now in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice.” Bossi’s drawings were in the style of Leonardo’s, and some were said to have passed as the master’s, without Bossi’s knowledge.

I called several prominent scholars in addition to Schröder to get their views. All spoke on condition of anonymity, and all agreed that the drawing was not the real thing. “I’m dubious,” one said. “It has been reworked greatly. Be very skeptical.” Another said he had seen the drawing a few years ago and didn’t think it was a Leonardo. A third also expressed doubts. “I haven’t seen the drawing, but on the basis of the photos, it didn’t look like a Leonardo.” He paused and added, “Maybe it is.”

Carmen C. Bambach, curator of drawings and prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is an expert on Leonardo and organized the exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman” in 2003. She was quoted in the New York Times in 2008 as saying that, based on a photograph of the portrait, the “work does not seem to resemble the drawings and paintings by the great master.” Bambach declined to make any further comment more recently.

Why do many scholars decline to be identified in attribution disputes? “Scholars usually don’t talk about other scholars,” said William E. Wallace, Barbara Bryant Murphy Distinguished Professor of Art History at Washington University in St. Louis and an authority on Michelangelo. “It’s a small world. I’m being approached all the time. I just don’t want to get into the fray. Maybe we have fragile egos and we want people to be our friends. It’s not fun to gather enemies.”

A Christie’s spokesperson issued the following statement: “We are aware of the recent discussions surrounding the possible re–attribution of this work which rely heavily on cutting–edge scientific techniques which were not available to us at the time of the sale and which even today are new and unproven. Until the debate has resolved itself and scholars are all in agreement we cannot comment on this particular work.”

Kemp said he had been sent a digital image of the drawing about a year ago “by someone acting for the owner. I thought it was likely to be one of the clever forgeries, but it did seem worth looking at the original. I did see it two or three months later in Zurich. When I saw it I thought, ‘Wow, this may really be Leonardo.’” But, he added, “even if you’ve got a fingerprint or whatever, you still have to do that old–fashioned thing—to say this is good enough to be real. It’s a subjective judgment.”

He said that the fingerprint on the drawing was compared with the prints on Leonardo’s Saint Jerome, in the Vatican. “There you can see he used his hands dragging the paint around the underdrawing. That is a strong indication that it was Leonardo’s fingerprints on the drawing and no one else’s.”

In an e–mail, Kemp added, “The print evidence has been hugely overplayed by the press. It’s only one supportive factor. If we didn’t have it, the case would still be solid.”

Leonardo left fingerprints on other works, according to Kemp. His portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., for example, is “plastered with prints. Every technical examination of a Leonardo pre–1500 to date shows use of his hands/fingers in painting. After that it becomes less obvious, but still occurs. The Saint Jerome prints are important because they are from an early unfinished painting and are part of the preliminary work, i.e. most likely to be Leonardo himself.”

Kemp said the fingerprint was discovered by Pascal Cotte, chief technical officer and cofounder of Lumiére Technology in Paris, which has developed a multispectral camera that produces images in extremely high resolution. Kemp then asked Peter Paul Biro to examine the drawing. Biro is cofounder of Art Access and Research in Montreal, where he is director of forensic studies, and he specializes in examining fingerprints for attribution.

“It’s a complicated process,” Biro, who said he had been trained as a conservator, told me. “It’s not possible to be 100 percent sure. It’s more a likelihood situation. The probability of those fingerprints being Leonardo’s is very high. It took me roughly three months to arrive at the observation that the fingerprint on the drawing can be compared to the fingerprint on Saint Jerome.”

Biro said in an e–mail that “there is another print on the drawing that was not possible to compare to anything I currently have in my database of da Vinci fingerprints. However, it is important to note that this edge–of–hand print is consistent with his application of ridge impressions found elsewhere on other works by him.”

In the last few years, Biro has attributed numerous paintings to Jackson Pollock on the basis of fingerprints he found on them, including a painting purchased for $5 in a thrift shop by retired Californian truck driver Teri Horton and a cache of 28 paintings said to have been discovered in a Long Island warehouse in 2002. All these attributions were controversial. Most scholars reject them, and other fingerprint experts have questioned Biro’s competence.

“It’s clearly business competition behind all this,” Biro said. “They are trying to smear my credibility.”

In an e–mail, Kemp wrote, “Paul has been the very model of clarity and probity in his research, never claiming more than is justified.” He said Biro had looked at the drawing “on his own account as an academic researcher rather than as commercial agent. He has received nothing from the owner for his work. I am backing him totally with respect to our project.”

Kemp has coauthored a book (to be published by the London press Hodder & Stoughton in March) in which he states that “by process of elimination,” the woman in the drawing is probably the young Bianca Sforza. He describes the portrait as exhibiting “indescribable delicacy and refinement.”

In the book, Kemp summarizes the reasons for his attribution to Leonardo. Among them are:

“The drawing and hatching was carried out by a left–handed artist, as we know Leonardo to have been.”

The drawing shows strong stylistic parallels with Leonardo’s Portrait of a Young Woman, in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. “Like other head studies by Leonardo,” the drawing has “comparable delicate pentimenti to the profile.”

“The proportions of the head and face reflect the rules that Leonardo articulated in his notebooks.”

“The interlace or knotwork ornament in the costume and caul corresponds to patterns that Leonardo explored in other works and in the logo designs for his ‘Academy.’”

“There have been some diplomatic re–touchings over the years, but the restoration has not affected the expression and physiognomy of the face to a significant degree, and has not seriously affected the overall impact of the portrait.”

A scholar of the Italian Renaissance who was asked to comment on the summary said, “Not one point in the summary is proof of the authenticity of the drawing. Leonardo was already a mature artist when this was said to have been done. He’s not going to be timid the way this drawing is. In the drawing the artist made a contour that outlines the profile. Leonardo would have built it up in light and shadow. The embroidery on her shoulder looks very mechanical. With Leonardo you would have seen the three–dimensional quality of her shoulder. Here it looks flat. It could have been made in the 19th century, not to deceive anyone but just as an exercise.”

Another scholar said, “If I were thinking of producing a fake, I would use vellum. It’s easier to get hold of than finding paper with the right watermark. As for fingerprints, if I leave a painting drying in my studio, anyone can pick it up and touch it. How can you say 500 years later that it’s Leonardo’s?”

The drawing was Lot 402 in a Christie’s sale of Old Master drawings in 1998 and was bought by Kate Ganz, a New York dealer whose parents, the late Victor and Sally Ganz, were prominent collectors of 20th–century art. The work was described in the catalogue as “German School, early 19th century. The head of a young girl in profile to the left in Renaissance dress,” executed in black, red, and white chalks with pen and ink on vellum, 13 by 9 inches in size. The estimate was $12,000– $16,000. The final price was $21,850, including the buyer’s premium.

“There are cases where everybody misses things,” an art historian told me, “but it’s a rare event. Normally with a sleeper, one or two people will spot it, but for it to be in a sale at a major auction house where everybody—collectors, dealers, curators, connoisseurs—see it and miss it does surprise me.”

Peter Silverman, who describes himself as a collector of paintings, drawings, and sculpture, specializing in Old Masters, told me that he believes he was the underbidder at the auction in 1998. He said he was in New York in 2007 with “my friend, a wealthy Swiss collector,” whom he declined to identify. The friend went to the Kate Ganz gallery, saw the drawing, and did not think it was from the 19th century, Silverman said. He bought the drawing for his friend for $19,000, he said.

I asked Silverman what he does for a living. “I used to be in publishing—books, language courses,” he said. He was born in Montreal and now lives in Paris and other European cities, he said.

Two dealers told me that Silverman is also a “runner” and a “picker,” which they defined as follows: “A runner is someone who literally runs from gallery to gallery, picking up something for x and trying to get y for it. A picker goes to every minor auction he can find and looks for discoveries, things that are underpriced.”

“I disagree with that appellation,” Silverman said. “I’ve made some of my best coups in major sales in front of everybody.” He said he bought a Raphael about 20 years ago at a Paris auction that had been sold as 16th–century Italian. “I paid about $10,000 and sold it for more than six figures.”

He said he took the drawing bought from Ganz to scholars, who told him it was a Leonardo, and to Lumiére Technology. He emphasized that he is not the drawing’s owner. “I make no secret of the fact that my reward will be not just in heaven if the owner decides to sell,” he said. “I also will reap all benefits of any Hollywood movie contract that may come along.”

The drawing is scheduled to be featured in an exhibition called “And There Was Light: The Masters of the Renaissance, Seen in a New Light,” at the Eriksbergshallen, an exhibition hall, conference center, and hotel in Güteborg, Sweden, from March 20 to August 15.

Will the world of scholarship reach agreement on La Bella Principessa in our time? “In general, scholars are trained to be skeptics,” said Wallace, the Michelangelo authority. “Part of our business is to ask questions and raise doubts. Consensus is rarely arrived at, and often it takes a generation or more. Since the beginning of the last century, no single object newly attributed to Michelangelo has gained universal acceptance by scholars—perhaps a drawing or two.”

Another scholar said of La Bella Principessa, “It won’t happen in our time.”

Kemp, however, is optimistic. “At the international Leonardo conference in Florence and Vinci last October, I heard no dissent, only praise for it,” he said. “I think it will be almost totally accepted once the book is out in March.”

The reattribution of paintings has been described as one of the light industries of the art world. The most reattributed artist is probably Rembrandt. In the last 90 years, the number of Rembrandts has dropped by more than 400.

Fra Filippo Lippi’s Portrait of a Woman and a Man at a Casement (ca. 1440–44), at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is one of the most reattributed paintings. At various times since 1883, the work has been attributed to Veneziano, Masaccio, Roselli, Uccello, Botticelli, and Piero della Francesca.

The late scholar Ulrich Middeldorf once explained in ARTnews why he was staying out of an attribution dispute. When he attacked the attribution of a sculpture to Michelangelo, he said, he was nearly lynched. “I walked away from that affair with a thoroughly blackened name,” he said.

I asked Wallace, “Since there have been periods in art scholarship of expansion and periods of contraction, where are we now?”

“We’re in an expansionist period,” he said. “It’s a lot of fun to discover Michelangelos and Leonardos. It also raises the prices.”

Milton Esterow is editor and publisher of ARTnews. Additional reporting by Judith Harris, Sylvia Hochfield, and Amanda Lynn Granek.

© 2019 ARTnews Media, LLC.